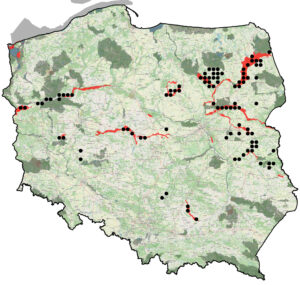

Curlew statistics: around 200 - 220 pairs are distributed through meadows alongside rivers, the majority in the east. The population has declined by 60% in the last 20 years with the main issues being agricultural operations like harrowing and silage cutting, and high levels of predation.

Location

In April 2024, Curlew Action visited Poland to see Curlew conservation in action. You can read our blog post from that trip. At that time there was no guaranteed funding, it was assessed year-by-year leaving the project unsure if they could continue their work.

However, later in 2024, an EU Life Project bid was successful which guaranteed money for five years for electric fencing, headstarting, land purchase, habitat management, predator control, and hardware like temperature loggers and GPS tags. I therefore returned in May 2025 to see this major plan start to unfold. My guide was Curlew researcher, Przemek Obłoza, and we also met up with Verena Rupprecht from the German organisation LBV, which has a project on meadow birds including Curlew and Black-tailed Godwit.

The first day was beautiful and warm, I was told the best day of the year so far. Poland has also been suffering prolonged dry and cold weather, as seen at Ławki Marsh (a large expanse of lowland fen and home to the rare aquatic warbler), which would normally have surface water, but not this year.

Over the next few days, we checked a number of Curlew nests in the Natura 2000 Pulwy Marsh, about 1.5 hours northeast of Warsaw, which we visited to last year, and we also visited two headstarting centres.

There are ten known breeding pairs in the Pulwy region, plus three single males. In the 2025 breeding season, a total of 14 nests were found, of which eight were first clutches and six were replacement clutches. In this local population, 35% - i.e. eight birds - are headstarted. This shows how important the headstarting programme has been for Poland, it has kept an endangered population going, buying time until the underlying factors can start to be tackled. In all, since 2014, over 700 birds have been released.

Nest Fencing

The electric fences are set at around 10m x 10m, which is a manageable size for one person to erect. All the fenced nests are in large, open fields, some are flower rich meadows under agricultural schemes, others are under some form of nature protection, quite a few are in more intensive silage fields. Agri-environment schemes restrict cutting the grass until mid-June, but that is early for Curlews as many seconds clutches will only just be producing young chicks. A lot depends on the relationship with individual farmers and how willing they are to help.

Each of the nests we visited through the day were intact with three or four eggs, some were just about to hatch, and in one nest we could see a tiny beak emerging, tapping at the shell; the other eggs were cracking. A further nest we checked was right by a road so couldn’t be fenced, however a drone showed it still had a sitting bird. The drone used was a DJI Mini 3, which is cheap and small.

When the chicks hatch they will leave the fenced area within a couple of days and their fate largely depends on what happens in the wider countryside. If they survive predation, how farmers work the land is vital to their survival. Land ownership is complex in Poland with farmers working long, thin strips (see previous blog), meaning one farmer may delay mowing, but an adjacent strip may be cut early. Curlew chicks are highly mobile from an early age and will wander widely across fields that may have multiple owners.

The Life project is making it possible to buy land from farmers who want to give up, or for abandoned land, which is the best way to guarantee that habitat can be managed over larger areas.

Fencing is really working in this part of Poland; the eggs are surviving to hatching, which is a great improvement. Last year, out of 8 nests only 1 egg hatched but the chick was predated before fledging, resulting in zero productivity in one of the best areas for Curlews in Poland. In 2025, nest after nest we visited has eggs on the point of hatching and due to the other work by the team, have a much better chance of surviving. Only time will tell if this is the case, and I hope we can keep you informed as we receive updates from Poland.

Predators

All the while we were accompanied by the most delightful birdsong from Nightingales, Golden Orioles, Hoopoes, different species of warblers, Whitethroats, and many more songbirds – and all of it was underscored by a host of singing, soaring Skylarks. The bird life was rich and vibrant and a joy to hear. Marsh Harriers hunted over the fields as did While Storks, Herons, Ravens, White-tailed Eagles, Crows and the ubiquitous Red Fox. Predation is always a major worry, not just from the many native species but also from introduced Racoon Dog, Racoon and Mink.

Przemek told me that birds of prey are not deterred by nest fences, and recently a Lesser Spotted Eagle has predated three fenced nests, landing in the middle and eating the eggs in situ. The eagle also checked out a fourth nest after it had seen a fox remove some eggs. The team are considering putting out decoy nests with bitter tasting eggs to try to deter it from wild nests. There are 2000 breeding pairs of Lesser Spotted Eagles in Poland, but they are not so common in the central area.

The EU Life project provides funds for fox control and so far, this year, up to 300 have been shot across the whole of Poland, with each fox earning the hunter about £40, paid for by the Life project. Is this level of control enough, I asked Przemek? He isn’t sure as there are so many foxes and only a year-on-year reduction in numbers across many landscapes will show results. He told me that when rabies was eradicated in foxes, (which were a major reservoir of the disease) by dropping meat laced with vaccine in the fields from the air, the fox population rose dramatically; we heard the same story when we visited The Netherlands. Rabies was a natural way to control fox numbers but now there is no effective way to cap the population (which is very good news for people and domestic dogs). I asked if the large number of top predators in Poland (2,500 wolves, several species of eagles, 300 Lynx) is having an effect on foxes, but he does not believe they do, there are simply too many and they are kept healthy all year on human and agriculturally generated food and warmer winters. The only way to control foxes is to shoot them and that is difficult, expensive and time-consuming.

Hunting in Poland is done by hunting clubs. The Polish team faces a difficult situation as some areas have many hunting clubs, making negotiations complex. Some clubs are helpful, others are more demanding. Organising predator control is proving to be another headache in Polish Curlew conservation.

Nest Cameras

The EU funding has also provided nest cameras (Browning Dark Ops Pro X 1080), which are proving invaluable. Some are deployed on fenced nests, others on unfenced nests to give the team a much better idea of why nests fail. One camera captured a group of free-ranging dogs racing over an unfenced nest and frightening away the adult which abandoned the nest. One of the exposed eggs was then eaten by an inquisitive dog, but fortunately, the other three eggs were rescued and taken for headstarting.

It is imperative to keep dogs under control during the breeding season. The photo below shows a curious dog inside a fence, which didn’t harm the bird or the eggs, but just its presence is enough to scare the bird away.

A survey in Poland found that 50% of farmers let their dogs roam free at night, which may cause significant disturbance in certain areas where ground nesting birds are vulnerable to all kinds of predation and disturbance.

Headstarting

Headstarting requires eggs to be collected from wild nests, and some of the first clutches are taken to be reared in safety in special facilities, allowing the birds time to re-lay and raise young naturally. It is an increasingly popular tool and Curlew Action ran an Online European Headstarting Workshop in February 2025.

Once they lay a second clutch the Life project provides the funds to protect the nests with electric fences and other measures.

The first headstarting facility is in the garden of an old farmhouse in the wonderfully named village of Wilczogęby, which means ‘the faces of wolves’. It is managed by Agnes Narowska, a local school teacher and biologist.

The eggs are incubated in a farm building alongside the youngest chicks, and the older chicks are reared in pens outside. In 2025, 46 eggs were collected, 36 hatched, three eggs stopped developing during incubation and six were unfertilised. One chick died during the hatching process and one shortly after hatching.

In a separate, heated box, three chicks were being kept warm under a lamp, ine was unable to stand and two were very unsteady. The cause of this is not known, but in other areas some similar chicks have recovered and fledged.

The older chicks ran around their outdoor pens looking healthy. (There appears to be no issue with choking in Polish birds, as in England). These Curlews will make their way into the Pulwy and Bug River populations and will be monitored carefully. Who knows if they will stay in the area where they will be released as it has now been found that a headstarted bird from the west of Poland has come to breed in the east.

The Polish birds are transported to an area and immediately let free, a so-called hard release. Many believe a soft release is better, where the birds are given time to acclimatise to a new area before being released, but it is more expensive and time consuming. GPS tagging has shown that in Poland, around 60% of released birds (n=62) were predated within a few days, most of them in the daytime, while 40% survived to undertake their first winter migration.

The second headstarting facility was in Cieloszka, a village about an hour and a half away from Biebrza National Park . It was bigger than the first and again located in a garden of a freelance ornithologist, Karl.

Here, 80 eggs were collected, eight were unfertilised, five did not hatch, five died after hatching, and nine chicks were suffering from some kind of issue to do with their legs and feet (but subsequently at least three of them have fully recovered). No one is sure why this is happening, but as the eggs were collected in a different part of Poland, it may be an environmental issue? It is being investigated at present. A few chicks have what is called ‘angel wings’ where the wings are not held close to the body but droop down, this is fairly common in captive reared Curlews and often treatable.

When these chicks fledge in various locations around Poland, their movements will be carefully tracked. En route to their wintering grounds some will stop at “Gutocha” fishponds, and area of wetland and sand dunes popular with fishermen as well as booming Bitterns, Reed Warblers and Whooper Swans. Up to 50 Curlews have been seen here.

Conclusion

Poland’s Curlews are in crisis, but the EU Life funding is holding out a lifeline. The team, both professional and volunteers, are doing a wonderful job and it gives us all hope for the future. The huge, overriding problems remain, however, and they are ones we share across Europe and the UK; how do ground-nesting birds live on farmland?

In some ways, we have it easier here in the UK as Curlew are greatly loved and embedded in culture, it is easy to find music, art and literature associated with them to allow an emotional connection to develop, but in Poland that is not the case. Curlew have never been a widespread breeding bird and are not well known. However, Curlews are seen as an important umbrella species that indicates the health of landscapes, as they do here in the UK; look after Curlews and so much else benefits.

Intensification of land is definitely increasing, a response to many different pressures from war to ideology to uncertainty about the future. It feels like the modern world turns its face against wildlife that has no economic value and cannot leave space and peace for creatures that simply exist alongside us.

Yet our practical concern for the vulnerable and the voiceless is a measure of who we are as a species and says more about us than fine words and paper-thin legislation. Only widespread agricultural payments on a landscape scale will enable farmers to do the right thing and sacrifice some land for these beautiful birds, but will this happen fast enough, and will we pay the right price?

The next European Curlew Fieldworker Workshop is now in the planning stage and will be held on Friday 6 to Sunday 8 February 2026 in Lancaster University. We will discuss in detail the practicalities of protecting Curlews as well as hold wider discussions. There will be time for meeting fellow fieldworkers to share ideas, problems, solutions and encouragement. Please join us, details will be released soon.

A huge thank you to Przemek Obłoza and the Polish Life project for organising such a fascinating and thought-provoking trip. And, as ever, thank you for supporting Curlew Action – every penny helps us spread the word, connect people and support nature education for everyone.