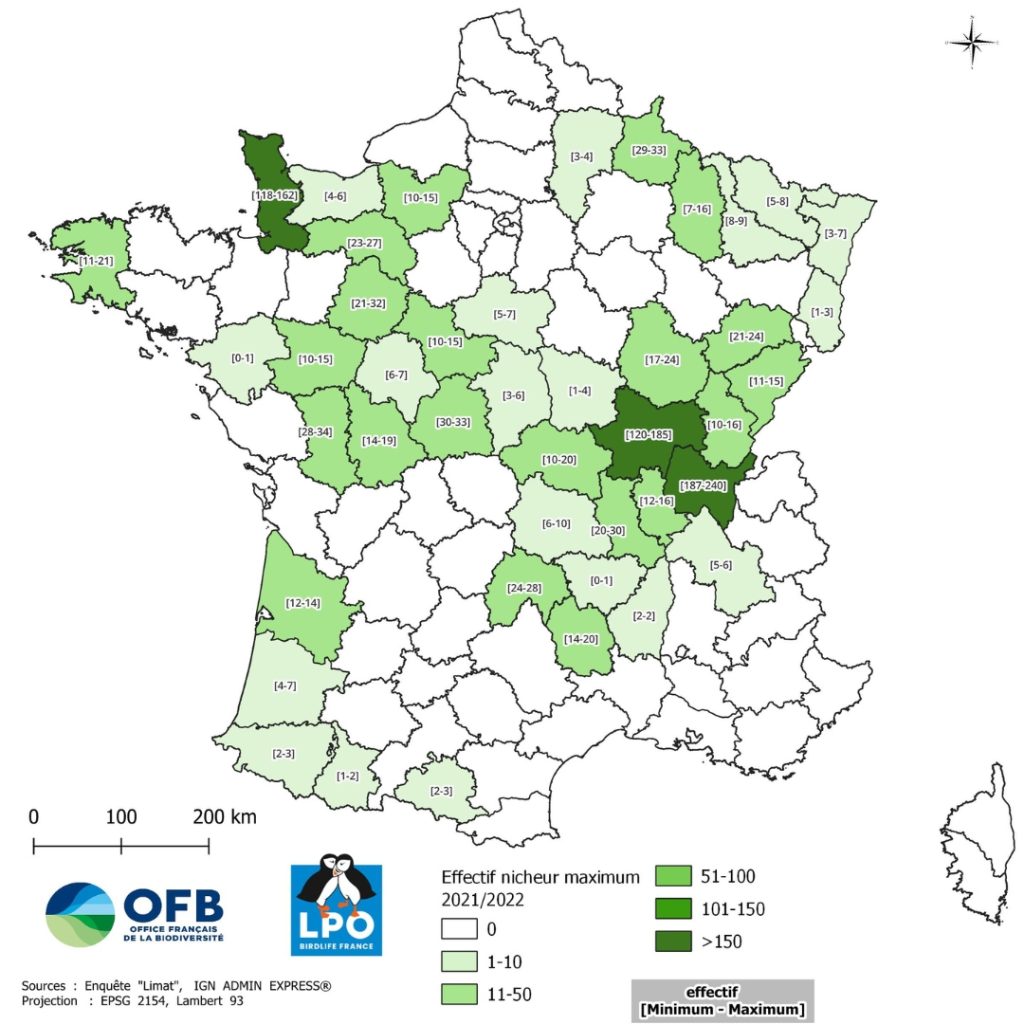

- French Curlews Statistics: Around 1,000 pairs across France but the larger populations are concentrated in two main areas: In the east - the Val de Saône (400 pairs) and in the northwest in Normandy (200 pairs). There are smaller populations in other regions. Almost all of them are in farmland.

- French Curlews mainly winter in southern Europe and along the coast of North Africa.

Background

The plight of Curlews in Europe was laid out before us on our visit to three regions in France in early June 2025. Across the European continent Curlews nest almost exclusively on farmland, with very few exceptions. This leaves the birds vulnerable to farming activities, which in turn are dictated by agricultural policy and local cultures.

European agriculture is intensive, large-scale and covers most of the land surface of this complex continent. Ground-nesting birds like Curlews are an indicator of the health of these hard-working landscapes. If they can survive, it is a sign that farming and wildlife are working together.

To this end, Curlew Action’s second European Curlew Fieldworker Workshop will be held between February 6-8th 2026 in Lancaster University. Details will follow soon. By exchanging ideas and solutions on shared problems with our European neighbours we can better protect Curlews and help many other species survive the harsh world of modern agriculture.

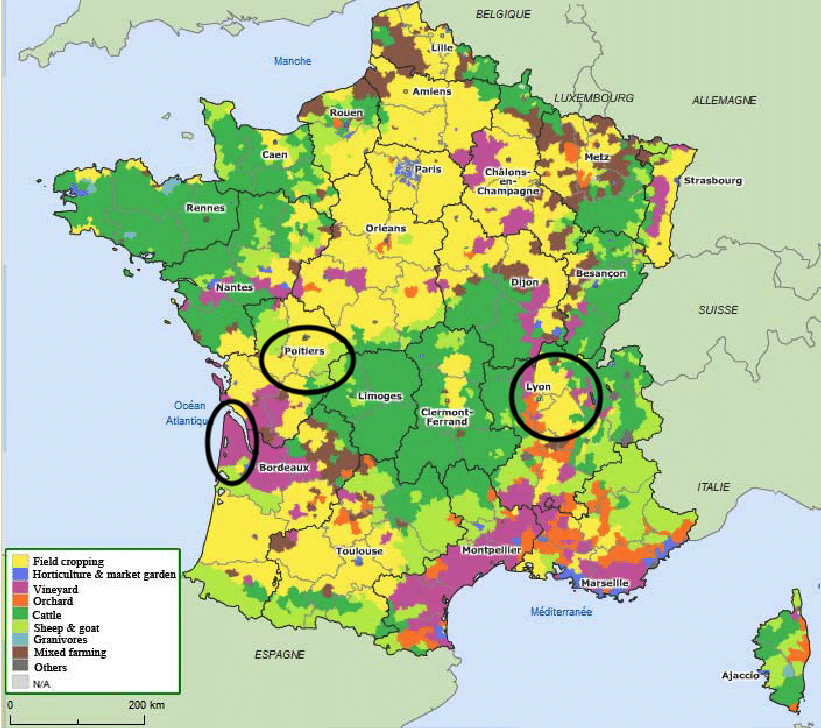

We visited Curlew locations in both the east and the west of France. In the east we saw large, flower-rich meadows in river floodplains which host one of the largest populations of Curlews in France, up to 400 pairs. This area also provides fodder for livestock, and the meadows are usually mown from late April to early May.

In the west we visited vast, open, dry grasslands which are also cut regularly, plus fields of crops such as maize (much of it for silage), wheat and barley. All this leaves little space or peace for birds like Curlews, Lapwings, Little Bustard, Stone Curlew, Skylark, Hen and Montagu’s Harriers, Grey Partridge and others.

Silage and crops are vital to the French economy. It is difficult to pinpoint an exact figure for silage production, but as France is the leading producer of beef in Europe, silage is a significant product, in the west, silage made from maize is very common. More than half of the country’s arable land is used for cereals and France produces a quarter of Europe’s total production. It is the fifth largest producer of wheat in the world.

French farmland provides habitats for both ground-nesting birds like Curlews and their predators, both mammalian and avian. In sharp contrast to the UK, any glance skywards reveals a host of raptors from Black Kites, Kestrels, Buzzards and both Hen and Montagu’s Harriers, which is an awesome and astonishing site for anyone from Britain.

We also visited Hourtin lake, which lies in the Aquitaine, to the northwest of Bordeaux on the Atlantic coast. Hourtin is the largest freshwater natural lake in France (nearly 62 sq km) and a roost site for Curlews from across Europe, either as a stop-over on migration or as a destination for the winter months; a few nest there.

It is also a favourite spot for hunting. As it stands, a moratorium on an annual take of Curlew during winter has been upheld for the past 5 years because of the increasing alarm over the declining Curlew population across Europe. This moratorium is voted on each summer. More details on hunting Curlews in France will be in a blog coming soon, but a brief overview is below.

At present, there is no national Curlew conservation programme in France, but there are well-organised projects in important Curlew areas which have an informal communication network.

Curlew Action was made very welcome, and we are grateful to everyone who showed us what is happening on the ground in one of the most important Curlew countries in Europe.

Location 1: Val de Saône

Mary Colwell and Flo Blackbourn met Nicolas Terrel and Charline Pierrefeu from EPTB.

We were also joined by Loïc Coat, a film producer making a documentary on Curlews, and Emmanuel Joyeux from the French Office for Biodiversity (OFB).

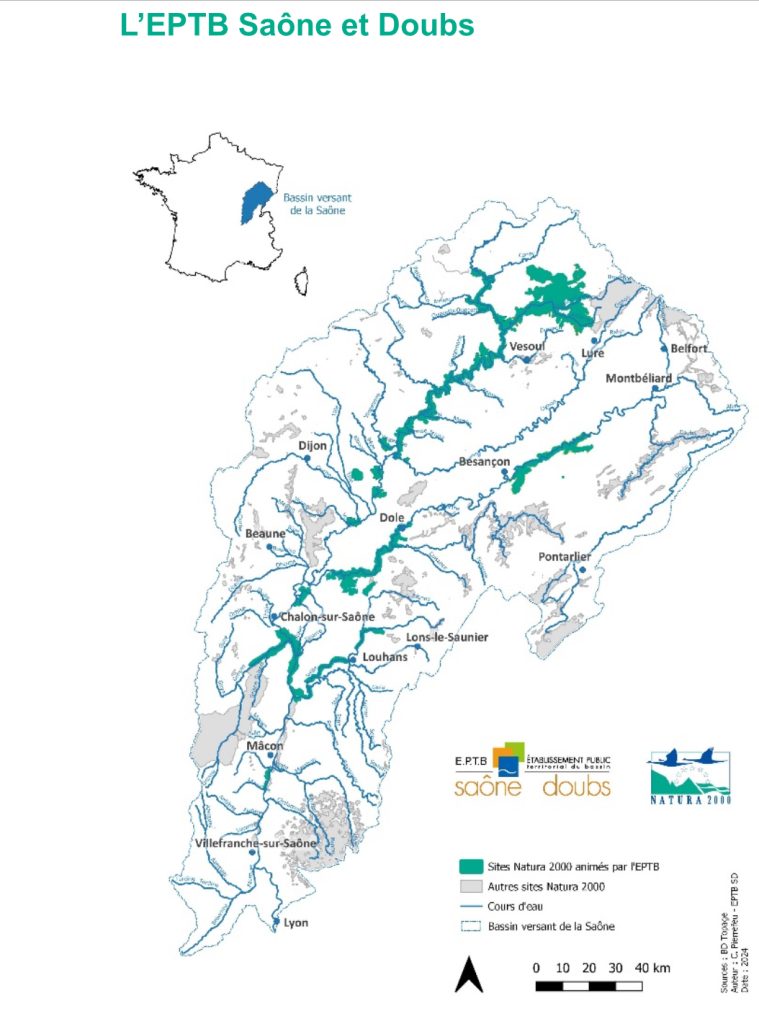

The Saône River is a 500 km long tributary of the Rhône, rising in the Vosges mountains and joining the Rhône at Lyon. Its floodplain meadows, which are wet for much of the year, provide nesting sites for around 400 pairs of Curlews, but the majority are found in Natura 2000 sites in the southern half of the Val de Saône. The flower-rich meadows are harvested as cattle fodder from spring onwards, while the cattle themselves are grazed outside the flood zone, or, in some cases, kept in sheds under a so called zero-grazing regime; like many other places, traditional livestock farming is in precipitous decline.

We arrived as many fields were being cut. On the outskirts of the town of Macon we watched a tractor mowing very fast (too fast) as Black Kites, White Storks and Cattle Egrets followed in its wake, hoovering up the casualties. There were 20 Curlew nests in the immediate area and at least one in this particular field, so communication with farmers is essential.

Many farmers who do have nests on their land have entered into agricultural agreements to delay mowing, but everything can be cut after July 15th. This delay in mowing causes a loss in fodder quality which is then compensated for by subsidies per hectare (around 400 euros per hectare, but the exact amount depends on the administrative region; some areas pay far more than others). So far, 600 hectares are under a delayed mowing arrangement.

The intensive mowing of the floodplains from spring onwards has also affected Corncrake. In 1980 there were 200 -300 calling males in the area, but in recent years the population has fallen to between 0 and 10 individuals.

Those involved in curlew conservation in this area don’t precisely locate each nest but use remote observation to determine a general area. There is therefore virtually no individual monitoring of broods and clutches. Only observations on post-breeding roosts before migration allow researchers to look for young.

Walking through a meadow to find a nest is not currently favored due to the fear of attracting predation by leaving visual or scent trails in the hay. There is, therefore, almost no direct intervention on the nests (electric fencing, nest cameras, weighing and measuring eggs etc); their work focuses on liaising with farmers and contracting out as much of the area as possible for late mowing.

In the northern Saône Valley, where the breeding success of Curlew is critically low, there is some electric fencing in the very small and isolated populations.

Some predator control is done by farmers and hunting clubs, up to 300 Foxes a year are shot in this area, as well as some Crow control. I asked if the returning Wolves would help keep Fox numbers down? The French Grey Wolf population is around 1100 in 28 packs, most of them in the southeast of the country. Their presence is unlikely to be significant as numbers are capped. Since 2020, the French government has authorised the culling of 19% of the wolf population, one of the highest rates in Europe, and this will be maintained in 2025, allowing 192 wolves to be killed. Farmers and hunters won’t tolerate their presence, fearing for their livestock and their quarry. It is hard to envisage anywhere in Europe allowing wolves to reach numbers high enough to impact the large and widespread fox populations.

As the success of Curlew nesting attempts is very difficult to determine in the tall, dense vegetation, the actual number of fledged chicks is not known in the Val de Saône, but it seems hard to imagine they do very well. We visited a nearby wet field where a flock of around 30 Curlews were feeding together. This number so early June is an indication that at least some, if not most of them, had already failed in their nesting attempts. A few of the birds would have been the non-breeders and juveniles who congregate around breeding areas each year, but no doubt the majority were failed breeders. It was a very sad sight.

I experienced the harsh reality of cutting grass for silage for myself at the next stop where we met a farmer in the process of harvesting a large field. He was sympathetic to birds and had a delayed mowing agreement and had left the next-door field uncut to protect a Curlew nest. It was impossible to see how anyone could find nests in these meadows; the vegetation was dense and high, and the fields were very large. This means, of course, that predators also find it difficult to locate the eggs. My concern was for the chicks, could they navigate the dense tangle of plants, and in wet weather, could they get dry?

The farmer agreed to take me on the tractor, which was a fascinating experience. Although he travelled slowly, birds such as Skylarks and Meadow Pipits burst from the grass in front of us, calling in alarm. A Brown Hare also ran for cover, and butterflies were fluttering all around. Kites and Egrets swooped around us. No matter how sensitively the cutting is done, it is still a brutal experience for meadow wildlife, and I was glad of the experience to see it for myself.

Coincidently, Pete Webster, a friend of Curlew Action and farmer on the border of the Yorkshire Dales and the Bowland National Landscape (Lawkland Hall Farm), had just sent me video of a huge silage cutter that was working in fields about 20 km away from his home in an area of nesting Curlew. The Claas Cougar 1400 is, according to the promotion material, “the largest self-propelled mower in the world with a 14m (46ft) cutting width capable of mowing 22 hectares (54 acres) per hour. 5 mowers - a triple combination at the front and 2 outrigger mowers on either side on telescopic booms can be individually adjusted, moved and manoeuvred for different land and situations.”

The tractor I was sitting on was miniscule in comparison.

The River Saône is the lifeblood of this region. It provides irrigation for a variety of agriculture, including the famous wineries based on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay grapes. Climate change is increasingly affecting farming as seasonal floods are more erratic.

This also impacts ground-nesting birds. The Curlew population was stable in the area until 2015 but has since declined. This may in part be due to the large and extensive flooding events of 2013, ‘16, ‘18 and ‘21, of the kind only previously seen every ten years, and where the water spreads over the floodplain to temporarily form a five kilometre wide lake.

Increased flooding is causing some farmers to give up grass cropping and switch to planting the ubiquitous Poplar, for which there are generous grants. Poplar plantations are a common site as they provide woodchips for a variety of uses such as fruit baskets, cheese boxes, cardboard, matches, quality paper, and for climate mitigation and flood prevention.

They do, though, present the same issues as any other large-scale planting of trees as monoculture, such as we see in the UK with Sitka Spruce. Plantations provide economic benefit, but they are ecologically impoverished and may deter ground-nesting birds from settling nearby because of the predators that either shelter or live there.

After the end of a long, hot day we stopped on a quiet road to see if we could find a GPS tagged Curlew. By this time, Emmanuel Joyeux and Nicolas Terrel had joined us. It was a beautiful evening, and the bird showed up immediately and behaved as though it had chicks, alarming loudly and flying in agitation until we moved away. Another ringed Curlew was also seen nearby, and while its identity couldn’t be confirmed at the time, it was believed to be an old bird.

As many as 50 others soon appeared, flying against the sunset, bubbling and calling ‘curleee’. There may have been some of the failed breeders we had seen earlier, but Emmanuel was heartened. “At least they are still here, at least we have a chance to help them. This makes me happy.” It was a magical sight and sound to end our first full day in France.

Location 2 – Deux Sèvres region of western France

A five-hour drive west of Macon took us to the region of Deux-Sèvres, which lies to the west of Poitiers. Three-quarters of the land is dominated by vast, dry grasslands for silage and arable fields growing wheat, barley and a variety of fruit and vegetables; it is much more agricultural in character than the Val de Saône.

Our guides to this region of France were Jeanne Bienvenut in the southern area, dominated by dry grasslands, and Christophe Lartigau who works in the northern region, which has more intensive agriculture. Both Jeanne and Christophe are with the organisation Groupe Ornithologique Deux-Sèvres (GODS).

There is more intervention at nest sites in this region, with electric fences, drones and nest cameras being used to help monitor eggs and chicks. It was heartening to hear that the team now uses Audio Moth recorders, which they heard about from David Jarrett at the Curlew Action Fieldworker Workshop in February 2024. These small and inexpensive listening devices are providing very useful information on what wildlife is present around the nests during the breeding season without having to do frequent direct visits. GPS tagging is also increasingly used. In total they have tagged 18 adults, 12 of them this year alone, which will provide vital information about the birds’ movements.

We began in the grasslands of the southern region, which are monitored by Jeanne. There are only 13 pairs nesting here plus a few non-breeders which hang around during the season. This year only two nests still have chicks, the rest have been lost to either grass cropping or predation. They have fenced six nests in all.

Jeanne is concerned at the number of eggs that fail to hatch and wonders if the large volumes of pesticides used on the grasslands are having an effect, and maybe the increasing age of the birds is a factor. In some nests three out of four eggs fail.

At times, she and others must balance competing conservation interests. Curlews and Little Bustards are sometimes found nesting in the same fields, but the date that they begin their incubation periods are different, the Little Bustard is a little later in May. The result is that if a field is under an agri-agreement scheme for Little Bustard, the farmer is allowed to mow until May 10th, but by then, Curlew may well be on eggs. Unless the team can locate and fence Curlew nests before that date, they may be lost. In another example, one large field set aside for nature had a Curlew nest, but it was cut early to help the botanical richness and the nest was destroyed.

But even with focussed and concerted efforts, Curlews are failing to thrive in this part of France. Significant time and energy go into protecting the birds, yet the fledging success is very low, between 0.1 and 0.3 (this means a pair will only successfully fledge a chick every four or five years).

Jeanne told us it can be a demoralising task to keep going, and she wonders if Curlews will ever be sustainable in such intensively managed landscapes. The needs of wildlife are hard-won in an industry with a focus on high yields. On the positive side, she finds that many farmers are willing to help once they know about nests on their land, giving hope that by expanding connections and raising awareness more sensitive farming practices can be established. It is a much a more difficult problem when it comes to tackling the very high levels of predation. Working with individual farmers to provide better quality habitat helps, but to be successful in recovering Curlew populations management must be done at scale and across landscapes through agricultural schemes paid for by the government; the overall problems remain huge.

The size of the area that Jeanne and others cover makes fieldwork demanding and tiring. Reacting quickly to a situation is very difficult and Jeanne can drive over 100 km each day just to visit the nests. The height of the vegetation is also an issue. Finding nests in waist high grass is difficult, even when it has been located by GPS tags.

We visited the northern area of Deux-Sèvres with Christophe Lartigau. I have never been to the Prairies of North America or Canada, but I imagine they are a little like the fields where Christophe monitors a range of ground-nesting birds, including Curlew, Little Bustard and Montagu’s Harrier.

Birds of prey are very common here, providing a magnificent and astonishing sight, although not all the species we saw are doing well. They undoubtedly do take chicks, and this year has been particularly bad for Curlew as the dry weather has reduced the abundance of other prey, increasing the likelihood of Curlew chicks being targeted. It was interesting to hear that Montagu Harriers don’t eat Curlew chicks and therefore Curlews and Montagu's nest close to each other.

Christophe believes there is also a problem in the region with feral cats, which they see on nest cameras.

So far, out of 22 nests, only one chick had fledged. From 68 eggs to only one successful chick is a very poor result.

He showed us a predated egg with a distinctive puncture mark in the shell, which could have been from a corvid.

The fenced nests were in vast fields of both crops and grasses. The fencing used is more like a mesh than strands of wire. They are sometimes flattened by wild boar or deer using their supporting posts for scratching. Money is a limiting factor; at present they only have the funds to fence six nests. This is a worry as Christophe regularly sees foxes, even during the day.

As the distances are so large and the fields so flat, huge and uniform, having a drone to find nests and eggs is very helpful. With a drone he can spot a nest in 45 seconds, it takes him 45 minutes at least by car and walking, and the time it saves, he believes, is the equivalent to having an extra person on the team.

He uses both thermal and photographic images to find eggs and adults. The drone flies at a height of 50 m to avoid disturbing the birds.

We talked through many of the issues affecting Curlews in his region. One is the lack of any payment to farmers to protect Curlew nests. He would like to see a payment of 10 Euros per nest, which should also be available for Stone Curlew. He also suggests that 25% of land could be given to nature protection on a rotational basis on farmland. Without legislation, agricultural payments and agreed targets for farmers it is hard to see how Curlews can survive in the long term.

But there are other factors, such as traffic accidents. To find food, Curlews and other species lead their chicks between fields and must cross the long, straight roads. Cars drive fast and casualties are common. We found a Little Bustard that had been hit by a car just after Christophe had talked about this problem. He would like to see an enforced speed limit during the breeding season.

Location 3 - The Landes heathland and Hourtin Lake

Location of Hourtin Lake, by Flappiefh - Sources of data: NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM3 v.2 & SWBD) (public domain); Directive Cadres) ur l'Eau;GEOFLA., CC BY-SA 4.0)

Les Landes Forest

Before the middle of the eighteenth century a million hectares of poorly drained heathland and moorland was occupied by shepherding communities who walked over the boggy ground on stilts and looked after as many as one million sheep. This once vast, wet blanket stretched from the River Garone in the north to the Pyrenees in the south. Much of it sits at 30m above sea level and slopes gently down to the coast where it slowly drained into the sea.

In June 1857, a new law ended this pastoral way of life and the whole area was drained, planted with vast swathes of Maritime Pines, or taken into agriculture, destroying this extraordinary culture and way of life. Today, the region is known as the Landes Forest. On a forest track in the centre of this forgotten landscape we met Margot Cornet, Christelle Charlaix from SEPANSO association, Estelle Jardot from the local watershed management agency and Claude Feigne, a volunteer who describes himself as an “Old Man, Old Ornithologist”!

It was a strange walk over a land transformed by brutal history. Patches of the old heath, now very dry and degraded, are all that remain of a vast landscape where thousands of Curlews used to nest. It was hard to imagine. The spikey, hummocky vegetation is impossible to walk through, so Claude can only search for birds from the sandy forest tracks or try to find bird footprints in the sand. Proof that Curlews were once very common is that the shepherds (so I’m told) used to eat Curlew eggs in an omelette on Easter Sunday.

Claude finds it a sad and depressing place. Goshawk nest in areas with new pines but disappear once the trees grow. The trees form the economic heart of the region with many people employed in the forestry industry, but the plantations are generally devoid of much life, and he finds that the local people are not usually engaged with nature. Trees are viewed as a crop and treated as such; this is not a nature reserve. There around 25 Curlew pairs in the region, but he has only ever found three nests and two chicks.

Claude told us that the future of Curlews in this region now relies on local military airfields where the birds can breed in peace. The number of breeding pairs and fledglings are not known due to a restriction on access, but outside of these protected zones he thinks it is a matter time before they no longer call over the remnants of heathland.

I asked if the area could ever be returned to the habitat it once was? No, he replied, not a chance. Forestry is too lucrative, and the land has been so comprehensively drained it would be difficult to reverse it over such a large scale.

But even if that were possible, French law states that when a forested area is cut down it must be replanted within five years. As government money is available for replanting, and two thirds of the forest is privately owned, it is impossible to change the direction of travel. The Landes Forest is here to stay, unless climate change takes its toll; already there have been devastating fires (we saw the charred remains of many trees) and the increase in storms has brought down large areas of trees. Only time will tell if this once unique landscape can emerge from 200 years of forestry, but for now the ghosts of the shepherds, and the Curlews, remain in the past.

Hourtin Lake

Our last stop of the day was to the large, inland Hourtin lake. It sits behind a magnificent line of dunes which protect it from the ocean. Fresh water and marshes are a magnet for water birds of all kinds, particularly on migration in the winter months. Some pairs of Curlews still settle here to nest. It is also a hotspot for hunters. Every 300 metres along the lake shoreline we saw hunting hides complete with both live and wooden decoys. The live ducks and geese quacked and called from their pens on the water.

Over a million ducks are shot in France each year, but, as concern for the declining populations of Curlews has grown, at present there is a moratorium on shooting them in the winter. This is very good news as Curlews from across Europe (as well as inside France) stop over on the French coast each year. The moratorium is voted on annually and we wait to see if it continues.

The marshland behind the lake is now a protected nature area, lobbied and fought for by the hunters to protect their quarry and the landscape. Without their backing it could have been developed as a holiday resort. The relationship between conservationists and hunters is not always an easy one in France, but as this example shows, it can work well. There is work to be done to build trust and a unified vision, but it was heartening to listen to our hosts talk about the efforts being made on both sides to find a way to protect birds everyone wants to see thrive. Everyone we spoke to thought that education, awareness raising and outreach were essential to increase people's understanding of the fragility and uniqueness of French wildlife, a message that is particularly important in schools.

Hunting in France is a complex mix of culture, class, revolution, sport, conservation and identity. A more comprehensive blog will follow, but maybe a French Curlew Action Plan will help provide a vision for the way forward?

A popular topic of conversation throughout the trip was whether France should instigate a specific national Curlew Action Plan, as is being finalised in the UK. A national plan for all waders is in the process of being drafted by the Tour du Valat and the OFB, and the Eurasian Curlew is included. This is very good news and could provide a structured way to progress, connect and support the different groups, and give the Curlew community a powerful and unified voice to help persuade governments to act. If written in collaboration with the hunters and farmers, it may bring all parties together so that everyone has a stake in the outcome. There is no doubt that the three Cs - Cooperation, Collaboration and Compromise - are the keys to success. Curlews are fiendishly difficult to protect, and everyone must be on board to succeed.

Once again, a huge thank you to everyone who showed us around, we had a fascinating visit and are grateful for your time and generosity.