A visit to see the new 25 million euro EIP (European Innovation Partnership) project for ten species of breeding waders, which runs for five years from 2024 to 2028. This project builds on the previous excellent Curlew work which laid the groundwork for Curlew conservation in Ireland. This is turn came out of the All-Ireland Curlew Workshop held in November 2016, a result of the 500-mile Curlew Walk.

The EIP is co-funded by the NPWS (National Parks and Wildlife Service) and the Department of Agriculture.

Mary Colwell and Flo Blackbourn from Curlew Action were guided by Owen Murphy, manager of the EIP.

Ireland Statistics: around 100 pairs of Curlews remain in scattered, isolated populations, a reduction of 98% since the 1980s. The main threats are similar to the rest of the UK and Europe – habitat loss, intensive agriculture (mainly silage production), forestry and unsustainable levels of predation.

Ireland is a country where history, culture and landscape merge, a potent mix that also shapes the landscape of the mind. When I walked through it in 2016 on my 500-mile walk for Curlews, Ireland seared itself into my heart for its complexity and its potential. My mother was Irish and I feel I have a deep connection. Big things have happened to this small island over the centuries - wars, colonisation, the clash of religions, grinding poverty and sudden wealth, and all of it is writ large, everywhere you look.

The Midland Bogs

Stepping onto a scrap of pristine raised bog in the Midlands, not far from the town of Athlone, we could sense what was once a vast peatland that covered central Ireland. Its glimmering pools and squelchy, sphagnum-rich terrain made walking hard going.

From back in the mists of time until the middle of the 20th Century, this land held hundreds, maybe thousands, of pairs of breeding Curlews, but relentless economic forces ripped it apart. Industrial extraction of peat to fuel power stations and for garden products joined forces with the mechanisation of peat digging for home use, and made peat removal fast and large scale. In addition, the conversion of land for farming was rolled out swiftly as Ireland’s agricultural economy grew. The result: this special habitat was reduced by 99%.

In the process of ripping away the peat the bodies of ancient bog-dwellers were unearthed, mysterious characters who had lain in its brown water and acid soil for centuries. What these ancestors saw and heard no longer exists, the myriad Redshank, Snipe, Curlew, Lapwings, flocks of geese and swans are now reduced to fragments of their former populations, if they are present at all; this is the 21st Century, a practically Curlew-free Ireland.

The used bog was often reseeded and used for cattle grazing and for fodder; the lowing of cows would have been familiar in the warmer months as they grazed by nesting birds. Curlews could hang on if the grass was cut late for hay and the drainage not too severe, but then progress stepped on the gas. Consumption of milk and meat rocketed and Ireland was there to meet the demand. Hedgerows were ripped out to accommodate larger machinery and to make more efficient use of the soil. Ever more drains were dug, releasing vast amounts of water into the rivers. The farmers worked so hard to dig drains that today’s new generation sometimes feel they are going against the wishes of their forebears by blocking them and rewetting the land.

In many places the cows have been moved off the fields and into sheds to spend their lives indoors. They are fed on silage made from fast-growing grasses which are cut multiple times a year, just when the birds are nesting. Their eggs and chicks are highly vulnerable to the blades, to the predators that feed across farmed landscapes and to the human disturbance from so much activity. In the place of wild, extensive peat bogs all too often there are monocultures and the scarred remnants of slashed, gouged and deeply damaged land. Curlew cannot live in this.

The four peat-fired power stations in central Ireland were built in the mid 20th C to bring jobs to this island’s empty heart, and it worked. I write about it in Curlew Moon, Chapter 5, when the power stations were still working. They were important sources of employment and essential for stable community life. I saw it for myself as I stood on the side of the road and watched the huge harvester ploughing up and down, stripping the land. But times change. In the last few years, concern for the climate and an acceptance that burning peat is a poor way to extract energy saw the industry switch focus.

There is no longer industrial scale extraction and the buildings are being repurposed for gas turbines or, in a twist of fate, storage for the batteries for the wind farms that are increasingly being stationed on the exposed land. The result is what we saw before us, broken down machines, overgrown railway lines, Nissan huts blown over in storms and peat bogs that have been flayed of their living skin.

Sitka spruce trees are dotted around the abandoned bogs, the seeds blown in from nearby plantations. In time, if left unmanaged, woodland dominated by introduced Sitka will establish. In other areas, though, restoration is underway. The invading trees are being removed and sphagnum moss replanted. Many of the drains are being blocked to bring back the life-giving pools of water, and with them a host of wildlife. The future is being made as we write.

No one can go back in time, and nor should we, but we can move forwards with vision and purpose. There has to be a way for the people, culture and wildlife of Ireland to thrive side by side. There will never again be the thousands of waders that once defined the soundscape of central Ireland, but there could be a lot more than at present. We could yet hear these liminal birds piping, fluting and bubbling in the infamous soft rain, and people could be trained to be economically involved in re-greening the land, but it will take a huge amount of public pressure and political will to make it happen. But it is possible.

A few pairs of Curlews still nest on the Midland bogs, but monitoring them is especially challenging. The landscape is flat, hummocky and fissured, making spotting a brown, grey bird on the muted vegetation hidden in a dip, nigh impossible. The black earth holds too much heat to make using thermal drones a good option, there isn’t enough contrast between the body of the bird and the land to provide hotspots. Training dogs to find nests is being trialled, or (getting back to basics) money could be found to pay for more people to use field skills. However it is done, monitoring is key to understanding what is needed.

Predator control is also difficult in such wide open spaces, but Owen is right, it involves far more than fences or guns, it’s about education, habitat management and commitment to a long-term strategy. The high numbers of predators are a result of the way we use land, and therefore it is up to us to find ways to reduce numbers to help Curlews. And of course, this is not just an Irish problem, high levels of predation are endemic across Europe for many of the same reasons.

What is certain, though, is that more information is needed about how the birds use this boggy land in the breeding season, which is best done by putting GPS tags onto them to track their movements. So far only four birds have been successfully tagged, but as the numbers build, so too will the information. Curlew conservation is a long-term project, and year by year the picture is more complete.

Money for expensive equipment is now, thankfully, available through the new EIP grant, and it will be fascinating to see how this develops and what is learned.

Lough Ree

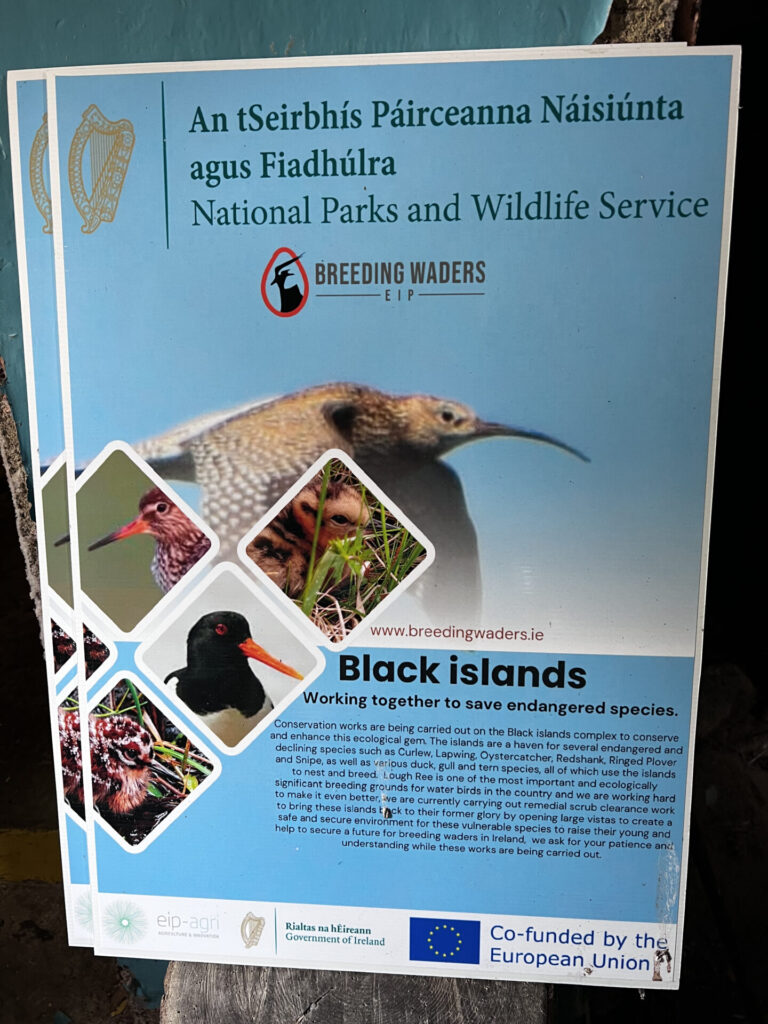

In 2016, the weather for my trip to the Black Isles in the northern end of this huge body of water was wild. The boat bounced and banged on the waves and the wind raged. We landed on both Nut and King Islands and the calls of Curlews were whipped away by the wind. Back then there was more scrub and tree cover, but some has now been removed to give the birds more space. There were two pairs of Curlews on King Island, the same as nesting there today.

As our boat approached the shore, a Curlew flew across the shingle, its large and laden brown body in contrast to the swirling clouds of white terns against the blue sky. It landed in long grass just behind a pair of Common Scoters floating offshore. There were so many birds calling and whirling, not just Curlews, but also Redshank, Common Terns, Black-headed gulls, Oystercatchers and different species of ducks. It is a thrilling place.

Water management is vital on Lough Ree, and the levels are dictated by both rainfall and policy. It is a frustration to conservationists that the water management plan takes into account the requirements of industry, leisure and water supply, but not wildlife. As the levels go up and down, nests can be left vulnerable, and even washed away.

Farmed for generations, a census in 1902 showed there were 25 people and three houses on the Black Isles, but they slowly moved to the mainland, with the last resident on the largest island, King Island, shutting the door on his cottage in 1986. Wild goats still roam free, but the other livestock left with the people.

A line of white-washed cottages is still there, complete with beds, fireplaces, old tables and pictures of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on the walls. They are capsules of old Ireland, the time of wildlife abundance and self reliance, I wonder what their world was like day to day, and how the wind and bird calls all around compared to what we hear now.

These islands are highlighted as release sites for the headstarted Curlews which are now coming on stream from the project based in the Fota Wildlife Park near Cork. Islands are easier to manage than the mainland, giving the newly fledged Curlews a better chance of survival. On a protected island, predator control and habitat management can be done without the constraints of agriculture, visitors or a constant influx of problems from the surrounding areas. The islands are owned by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, which will shield them as much as possible from the developing world all around.

As we ate lunch, sheltering from the squalls and wind, we discussed the problems faced by Curlews in Ireland. Mark Craven, a predator control specialist who I met in 2016, told us he removed many mink from King Island when he first started, as well as the occasional fox. We found two gulls that had been killed by a bird of prey. The mink are the biggest issue, though, with a stream of them swimming across from the mainland.

Fox numbers are very high throughout Ireland, the numbers increased as lacing carcasses was banned (thank goodness). Today, fewer farmers do their own fox control as chicken coops for home use are less common. The increase in forestry is also thought to be a factor, as well as warmer winters, sheep nuts and human littering. It all adds up, putting untold pressure on birds that nest on the ground. If we want birds like Curlews there is no alternative but to try to keep fox numbers at manageable levels. Understandably, this is a hard message for many people to hear, and why nature education and raising awareness of the issues is vital across society.

Before we left the Black Isles we went to the small, privately owned island of Inchbofin to visit Mike Connell, the landowner and farmer, to see where a soft release pen for the headstarted chicks was to be situated (it is now in place). The nearly fledged Curlews will spend two weeks in the pen by the sea, acclimatising to their new surroundings and fixing their position with the stars. It must be an emotional sight to see them lift off on the breeze and head out to a land full of opportunity and many dangers. Statistics tell us that only 40-50% will survive their first year, which may mean only ten birds will be added to the breeding population, but that is ten more than would otherwise be flying free, and all we can do is hope.

Shannon Callows

As the magnificent River Shannon spreads out and relaxes across the central basin of Ireland it creates a semi-aquatic world of meadow, flood plain and temporary lakes that fill and empty with the seasons – a landscape called the Callows.

There is half submerged land and water-drenched air all around, a world of wildlife and spirits of the past. The flooding and receding of the river is the life blood of the land, but where the water ends and the grass begins is as fluid as the folklore that surrounds it. Sailing downstream you feel part of this Avalon world, just one more living being amongst many that appear and disappear amongst the reeds. Sit back for long enough and a Celtic goddess or a white monk might drift by.

‘The three oldest cries in the world are the wind cry, the water cry and the curlew cry,’

wrote Yeats, and one did call as we landed on Inishee in the centre of the river. This is a rounded hump of land, only 30 hectares, which totally submerges in the winter. I also visited here in 2016 to see a large electric fence that had been erected right around the perimeter to protect the rapidly declining waders from predators swimming out from the mainland. It worked well and numbers increased rapidly, especially the Redshank, but then the funding ran out and the maintenance of the fence became too difficult to keep up and it collapsed, leaving a raised mound covered in vegetation - a 21st Century midden.

I have seen this many times, good ideas that founder on the rocks of conservation timescales, failed grants and empty funding pots. Part of the EIP bid is to repair or replace the fence, but it is hard to know whether the same will happen again after this opportunity has passed. Will the Shannon’s relentless flood cycle render an electric fence unworkable and force the island to return to its watery state? The detritus from conservation can be found right across Europe and the UK in the remnants of projects that once seemed so full of hope.

In the meantime, predator control is done by John Kenny who tries to keep on top of the Foxes, Mink, Pine Martens and crows. In the past, Mark Craven told me he had dispatched 23 mink in one year, just from Inishee.

In the year 2000, this island once hosted 23 calling male corncrakes, but increasing severe flooding at the wrong times of the year saw them out, and no doubt affected other birds, too. Climate change is making the floods unpredictable and severe. Water management for hydro schemes and other demands make this an increasingly challenging place for birds to nest on the ground, but I hope new initiatives succeed in giving them the security they need. Many decades ago there were so many nesting Curlews around here that one author described them as virtually colonial. Three or four pairs are dotted across the islands now, their voices summoning up images of the past and calling to the future.

Fota Wildlife Park Headstarting

The headstarting projects now found across Europe are a response to a crisis. The birds are failing and it is easier to keep populations going than reintroduce them once they have disappeared.

For Ireland, they provide not only chicks but a sense of hope in the darkness. The decline of Irish Curlews has been so rapid that extinction is a real possibility in just a few years. Of all the Western European countries, Ireland’s situation is the most serious. Keeping birds flying by priming it with headstarted chicks buys a bit more time to tackle the huge and systemic problems, and that has to be worth a go.

The main issue is sourcing enough eggs. There are so few wild ones that the number of fledglings is low, and not all of them will survive their first year. The project would like to source British eggs, perhaps from grouse moors where the Curlew populations are healthier.

We watched this year’s 14 chicks running around, and there are still four left to hatch at the time of writing. Last year, 36 eggs were collected, so that is quite a drop. There will be good and bad years, but too many bad ones could be disastrous.

To stabilise the population, Ireland needs to fledge a hundred or so chicks each year, but at present it is no more than 10-20. But there is still hope, and if more eggs can be found Ireland’s Curlews could yet turn the corner.

I ask Owen Murphy and Mark Craven what Curlew success looks like – do they have a figure in mind? They told me that success isn’t simply an increase in fledged chicks in the present, but long-term policy and societal changes changes that are sustainable in§to the future. Improvements that have an end date and then stop dead are often not worth doing, they simply “prolong the agony” as they put it. But creating lasting change would be a sign of real success, the foundation stones for building a better future.

One of those building blocks is a change in agriculture. Farmers who are taking the right steps to conserve wildlife on their land and practice nature friendly farming often feel they are going it alone – not working with other conservationists, not supported by their neighbours, and not appreciated by those who purchase their food. The EIP team and many others want to find a way to acknowledge them and make nature-friendly farmers feel more involved and appreciated by the political system and society.

On a positive note, we were told by Owen and Mark that they feel the 2016 Curlew walk re-energised Curlew conservation in Ireland. Although the birds were in dire straits, not much was happening because there was very little money to do any practical work. It was heartening and emotional to hear that much of the progress that has been made would not have happened but for the impetus created by the walk and the subsequent all-Ireland Curlew conference held in the Midlands in November 2016.

I love Ireland, its landscapes, people and the evocative culture that stretches far back in time. If the EIP succeeds in building on the excellent work that has gone before and utilise the passion and expertise that is found throughout the country, these precious birds can be saved. We will keep you informed.

Thank you to Owen Murphy and all the people we met who were so welcoming and kind. We are with you every step of the way.