Written by Charlotte Varela.

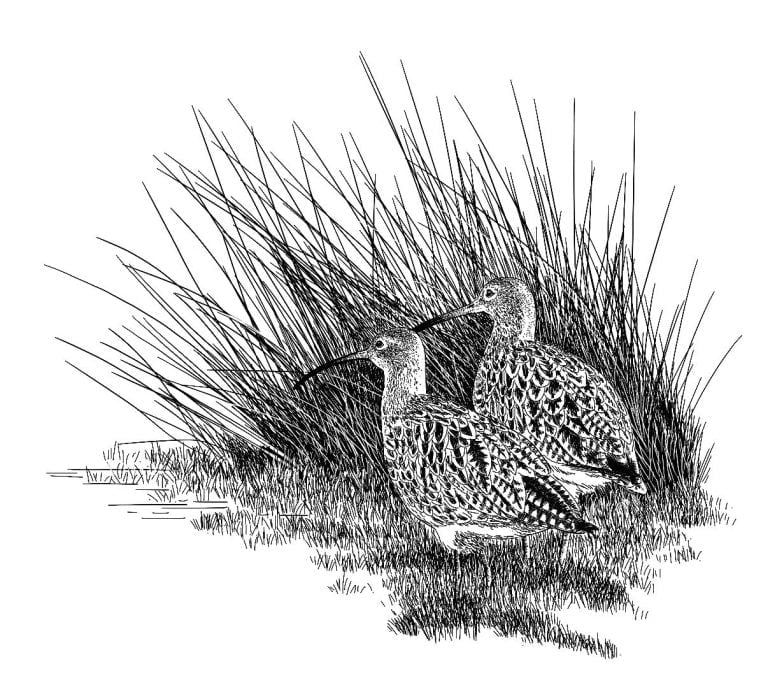

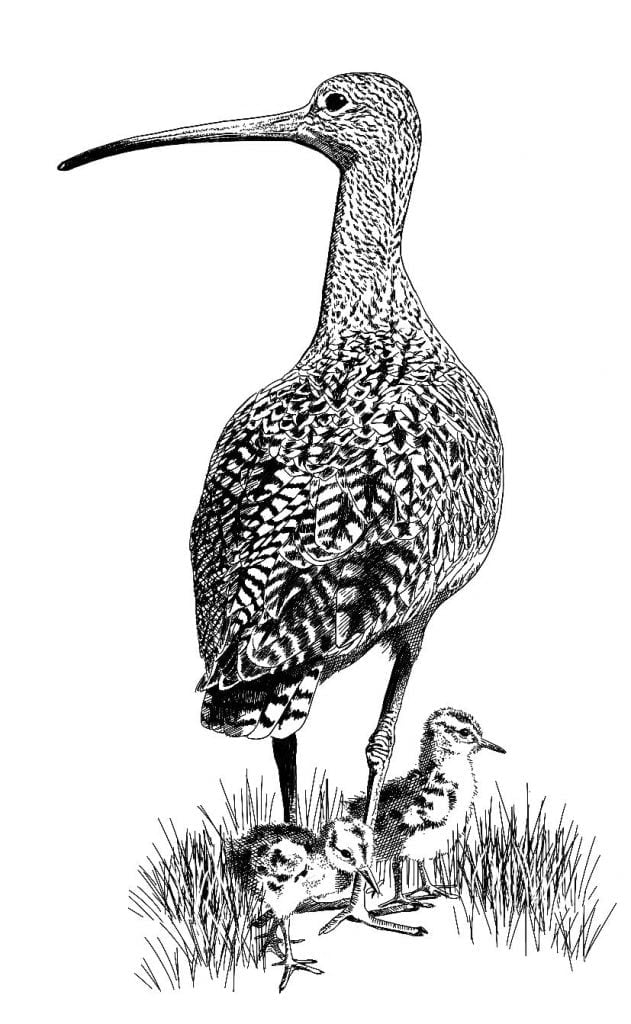

Illustration by Jessica Holm.

From lapwings in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights to the titular raven in Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven, birds have long acted as inspiration for literature. Some are used to evoke a sense of freedom and wildness while others are an ill-omen, foreshadowing tragedy. The curlew, however, has long evoked a whole spectrum of human emotions.

Sadness, longing, joy – they can all be found in the call of the curlew, and it is this call that lodges deep in the hearts of poets, authors and story tellers. Take W. B. Yeats, who gave the curlew a starring role in several poems.

In He Reproves the Curlew, an escape into the supposed sanctuary of nature is tainted by the sorrowful call of our largest wading bird, causing the narrator to cry:

‘O curlew, cry no more in the air,

Or only to the water in the West;

Because your crying brings to my mind

passion-dimmed eyes and long heavy hair

That was shaken out over my breast:

There is enough evil in the crying of wind.’

While modern nature writing uses nature largely as a vehicle for escape, He Reproves the Curlew highlights how the natural world can also brutalise our emotions. The curlews ‘love weep’ embodies Yeats’s yearning for a love now lost and which he may never truly recover from – we will find our grief echoed wherever we turn.

But Yeats wasn’t always so critical of the curlew. In his poem Paudeen, the fluting exchange between a pair of curlews softens his spite for the local shopkeeper and makes him realise that both he and ‘old Paudeen’ are human after all:

‘Indignant at the fumbling wits, the obscure spite

Of our old Paudeen in his shop, I stumbled blind

Among the stones and thorn trees, under morning light;

Until a curlew cried and in the luminous wind

A curlew answered; and suddenly thereupon I thought

That on the lonely height where all are in God’s eye,

There cannot be, confusion of our sound forgot,

A single soul that lacks a sweet crystalline cry.’

Dylan Thomas, too, was inspired by the sound of the curlew. His sensual poem, In the White Giant’s Thigh, begins with a scene-setting curlew call:

‘Through throats where many rivers meet, the curlews cry,

Under the conceiving moon, on the high chalk hill,

And there this night I walk in the white giant’s thigh

Where barren as boulders women lie longing still

To labour and love though they lay down long ago.’

Some have described the curlews call as sounding like a grieving mother crying for her lost child, and in this instance, it is used by Thomas to mourn not lost children, but children that will never be. In the White Giants Thigh brings to life a superstition that infertile women could conceive if they made love in the thigh of the white giant on the chalk hill at Cerne Abbas. ‘They yearn with tongues of curlews for the unconceived’, Thomas writes.

Curlews also play a central role in setting the scene in From Under Milk Wood. Thomas’s love for the curlew is best summed up by close friend and fellow poet, Vernon Watkins who, following Thomas’s death, wrote:

‘Sweet-throated cry, by one no longer heard. Who, more than many, loved the wandering bird.’

More recent literary lovers of the curlew include Ted Hughes. Growing up in, and later living around the Calder Valley and Pennine Moors, the spring and summer soundtrack of curlews served as a lifelong inspiration. For Hughes, their call was something to be revered and a symbol of true wildness. He wrote:

‘Curlews in April hang their harps over the misty valleys. A wet-footed god of the horizons.’

Curlews also feature in his poem Emily Brontë, where he uses this bird of the moors to bring Emily’s dependence on the wild, untamed landscape to life with the line: ‘The curlew trod her womb.’

Hughes even wrote an entire poem dedicated to the curlew, titled Curlews Lift. He depicts the moment the birds take flight, shedding their upland camouflage and dissolving into the haze. It is incredibly evocative, and at a time when my own local curlews have fled to the coast, makes me long for their spring return:

‘Out of the maternal watery blue lines

Stripped of all but their cry

Some twists of near-edible sinew

They slough off

The robes of bilberry blue

The cloud-stained bogland

They veer up and eddy away over

The stone horns

They trail a long, dangling, falling aim

Across water

Lancing their voices

Through the skin of this light

Drinking the nameless and naked

Through trembling bills.’

Illustrations by Jessica Holm.